The weaponization of tariffs by US President Donald Trump has clearly generated fear and loathing…

The Remittance Shock C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

The fall in remittance flows following the loss of migrant jobs in leading host countries has been among the many adverse effects of the Covid crisis on developing countries. While there have been job losses across the board in regions and countries hosting a large proportion of the world’s migrant workers, job losses for foreign workers have been greater than those for domestic workers in most. Moreover, a major region hosting international migrants, constituted by the Gulf Cooperation Council countries, has seen economic conditions worsen also because of the steep fall and continued low level of oil prices. As is to be expected, the countries most affected are the low and middle income countries, remittances to which are projected to drop by 7 per cent from $548 billion to $508 billion. But underlying these aggregate figures are significant differences, with extremely adverse implications for some countries.

News reports on the traumatic experiences of migrants who lost jobs but could not return home because of the transportation lockdown highlighted the personal crises that the Covid shock generated among these sections. But soon it became clear that the external effects of the crisis that affected these workers individually could also overwhelm whole nations, given the importance of temporary work abroad for sustenance of families through remittances, and the importance of aggregate remittances for whole economies.

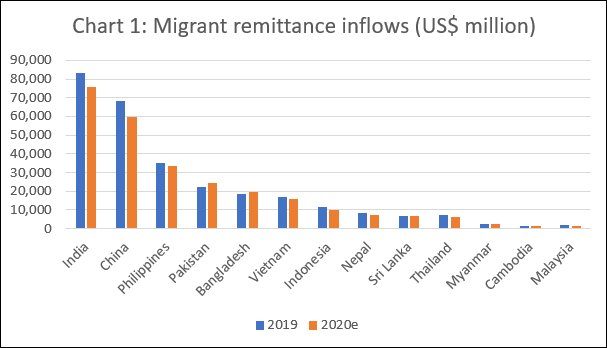

Asia was affected particularly adversely. Ten Asian nations, each receiving more than $10 billion in remittances in 2019, accounted for close to a half (47 per cent) of all remittances to all low and middle income countries, and more than a third (36 per cent) of the global flow of remittances (Chart 1). According to the World Bank’s estimates, India was the leader with inflows in excess of $84 billion in 2019, followed by China, Philippines, Pakistan and Bangladesh. Within Asia, South Asia seems significantly more dependent on migrant remittance inflows. In fact, after Bangladesh, absolute remittance inflows taper off quite significantly.

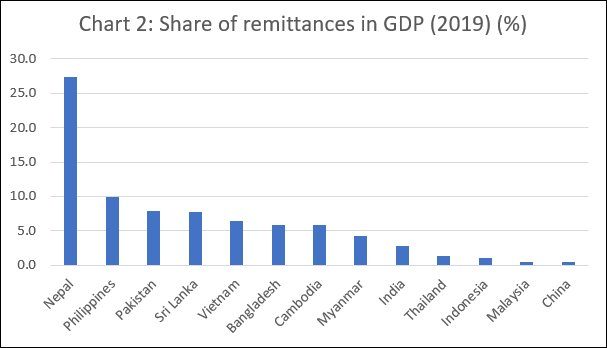

However, absolute levels of inflows do not capture the extent of vulnerability of each country. Given differences in size as measured by GDP, the importance of remittances for different economies varies considerably. The $83 billion of remittances to India in 2019 amounted to just 2.8 per cent of its GDP, whereas the $8.2 billion that flowed into Nepal amounted to 27 per cent of its GDP (Chart 2). In terms of significance relative to GDP, after Nepal, the countries that seemed vulnerable to any decline in remittances were The Philippines, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, Vietnam, Bangladesh and Cambodia, where remittances amounted to between 5-10 per cent of GDP. Most of these are the smaller (and in some cases, weaker) economies in the Asian region.

However, even this dependence on remittances relative to the size of the economy does not capture vulnerability in full. To start with, within large economies, remittance flows tend to be concentrated in some regions, as in the state of Kerala in India, making remittance flows as a percentage of state domestic product quite high. Out of the $83 billion of flows to India in 2019, Kerala is estimated to have received around $14-15 billion, which amounted to around 30 per cent of the state’s gross domestic product. So even if India as a whole may not be too affected by the remittance shock, states like Kerala would be.

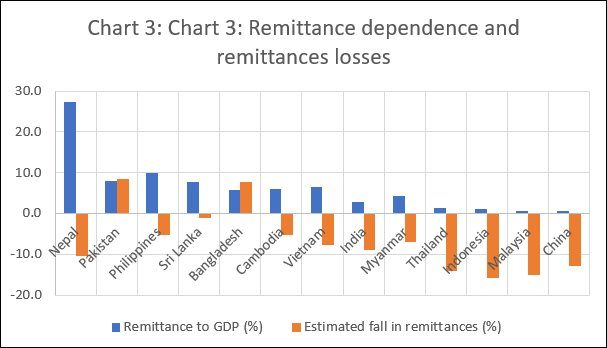

Secondly, projections seem to suggest that the reduction in remittance flows can vary significantly across countries, and may not even occur in some countries. Nepal, which is heavily remittance-dependent, to the tune of 27 per cent of its GDP in 2019, is expected to record a fall in remittances in 2020 of more than 10 per cent. India is expected to record a fall of close to 9 per cent, but remittances constitute only 2.8 per cent of its GDP (Chart 3). Interestingly, Sri Lanka is projected to experience a loss in remittances of just one per cent, and Pakistan and Bangladesh are expected to record increases in remittance flows, even if not of the same magnitude seen in earlier years. One reason for differences in the decline of remittance flows could be differences in the dominant destinations of migrants and the occupations they are concentrated in, since destination countries vary in the intensity of the unemployment crisis resulting from the pandemic and associated freeze in economic activity.

But this cannot explain the increasing remittances in Pakistan and Bangladesh. The World Bank’s October 2020 Migration and Development Brief 33 attributes the post-Covid increase in remittances to these countries “at least partially” to what it refers to as the “Haj effect”, with migrants remitting home the money saved from the postponement of the pilgrimage to Mecca, due to a significant reduction in the number of Haj visas issued in the wake of the pandemic. If true, this implies that the figures for these countries do not reflect the actual impact of the pandemic on the earnings and capacity to repatriate funds of migrants from these countries.

Adjusting for these factors, it emerges that the smaller and poorer countries are the worst affected. The adverse impact is not fully captured by the fall in the remittance to GDP ratios because the effect of a fall in remittances that reduces the numerator is partly neutralised by the fall in GDP resulting from the crisis. Combine that with the role that remittances play in delivering foreign exchange crucial to finance essential imports, and the adverse balance of payments effects that a decline in remittances can have, that impact is even stronger.

Therefore, the transmission of the damaging effects of the pandemic-induced crisis through this route can be a matter for serious concern for small and poor developing countries like Nepal. This strengthens the case made on various other grounds for an international response involving debt forgiveness and substantially enhanced additional concessional assistance particularly to such countries.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on November 17, 2020)