Read the Concept Note South Africa’s G20 Presidency (2025), for which this call for papers…

Finance Capital, GDP Growth and Sri Lanka’s Economic Depression Ahilan Kadirgamar

There is an emerging international debate about what is at stake with GDP growth. In Sri Lanka, not just nationally, but even at the provincial level, GDP growth and contribution are attributed to economic success. However, the focus on GDP growth without considering the impact on employment and livelihoods, and for that matter social welfare more broadly, can lead to rising inequalities and even dispossession.

Sri Lanka’s economy needs to grow out of the economic depression and the state has a major role to play in this expansion

This was the theme of a workshop organised at the Chulalongkorn University in Thailand by the International Development Economics Associates (IDEAs) and Oxfam, titled ‘Beyond GDP Growth and Against Neoliberalism.’ This column is based on my presentation at the workshop delving into the vagaries of GDP growth in Sri Lanka.

Neoliberalism and the 1970s Crisis

Sri Lanka was known as a model development state in the 1970s for its high Human Development Indicators despite its low per capita GDP. That was mainly due to the free education and healthcare policies as well as universal food subsidy dating back to Independence. However, such advances began to decline when Sri Lanka became the first country in South Asia to implement neoliberal policies in the 1970s.

Neoliberalism as an ideology of free markets gained ascendancy with the global economic downturn in the 1970s. Keynesian policies of state intervention towards full employment that was dominant during the post-World War II economic boom became delegitimised with the widespread capitalist crisis of falling profits. Neoliberalism, in effect, became the class project of finance capital to ensure higher returns for financiers through state intervention. The IMF, the World Bank and the WTO became the international agents imposing this class project on developing countries.

Neoliberal policies entailed privatisation of public institutions, the break-up of trade unions, and agreements along with state structures to integrate national goods markets and financial institutions with global systems in the interest of finance capital. Furthermore, cuts to social welfare became the norm, and sometimes even outright privatisation of education and healthcare. Such economic reforms often lead to an initial bout of high GDP growth with the inflow of capital creating a bubble, but it declines when the bubble bursts. In Sri Lanka, the economic troubles that came with the unravelling of the bubble coincided with the onslaught of the civil war in 1983.

Second Wave of Neoliberalism

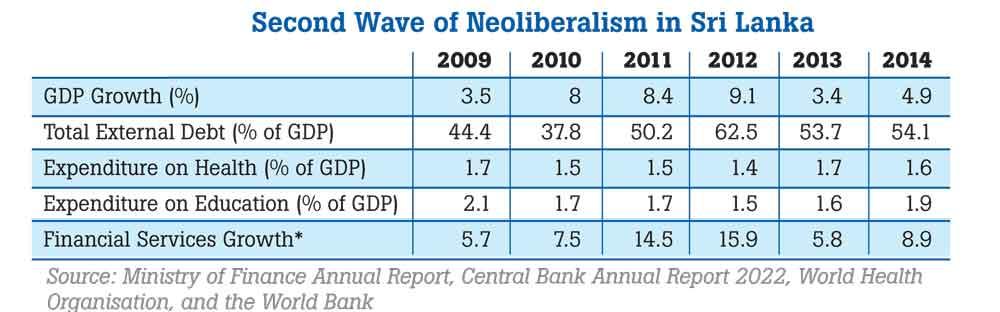

In this context, successive Sri Lankan governments could not accelerate liberalisation as the disruptions of the civil war preoccupied the state. It is at the end of the civil war in 2009, with the conjuncture of a global financial crisis and militarized stability in the country, that neoliberal policies were taken forward along with tremendous inflow of global capital into the country. Sri Lanka had the best performing stock market in the world in 2010, with the Colombo Stock Exchange index increasing by 250 percent. Furthermore, large infrastructure projects and investment in real estate funded through external debt from 2010 to 2012, led to high GDP growth on the order of 8 to 9 percent. While many analysts considered Sri Lanka a success story, I alerted the crisis prone character of such GDP growth propelled by finance capital in an article titled ‘Second Wave of Neoliberalism: Financialisation and Crisis in Post-War Sri Lanka’ (Economic and Political Weekly, 2013)

While I was preoccupied with Sri Lanka, I realised the same characteristics of neoliberalism, financialisation and GDP growth were also the case in the United States. Deepankar Basu and Duncan Foley, in a rigorous paper titled, ‘Dynamics of output and employment in the US economy’ (Cambridge Journal of Economics, 2013), unpacked the problematic role of the financial sector in the calculation of the GDP growth in the US economy. This is how Basu and Foley described the economy under neoliberalism:

Sri Lanka had the best performing stock market in the world in 2010, with the Colombo Stock Exchange index increasing by 250 percent

“From a longer term labour perspective, the weakening of the relationship between measured real GDP growth and employment poses serious questions about the social and political viability of what we call ‘neoliberal’ globalising strategies for economic development in the United States and other economies. These neoliberal strategies include liberalisation of international trade and capital flows, de-regulation of financial markets and institutions, reliance on inflation-targeting monetary policy, privatization of traditionally public sector economic functions, weakening of job security and workers’ rights to organise, reduction in job safety and health protection and unqualified reliance on markets for the allocation of social resources. Understanding the changing relationship between output, conventionally measured as real GDP, and job creation (and unemployment) is a necessary first step in fashioning policies that can simultaneously generate growth in employment and protect labour interests such as the right to collective bargaining, adequate wages and benefits, acceptable working conditions and adequate and secure pensions, within the framework of democratic political institutions as alternatives to neoliberal economics.”

In other words, in Sri Lanka as in the United States, the question arises as to whether GDP growth leads to actual job creation or is merely a signal of higher profits for finance capital. That of course depends on the structure of the economy, which itself changes with neoliberal policies.

In Sri Lanka, high GDP growth in the early 2010s came with the inflow of finance, leading to an increase in external debt stock. That boom came with the growth in financial services and expansion of the construction sector, but contraction of spending in education and health. Financialisation leading to the proliferation of Finance Companies also led to a burgeoning microfinance sector resulting in mass indebtedness and dispossession of women.

GDP and Extraction

The larger point I want to make is that when we look at GDP, we need to consider its substance, rather than fetishize its growth figures, which can merely serve financial extraction and even lead to the kind of debt crisis that has now engulfed Sri Lanka. Next, despite the attack on neoliberal ideology of free markets, as with the rise of right-wing populists around the world including the forceful return of Trump, finance capital is still reigning supreme.

Sri Lanka now mired in an economic depression with the GDP having contracted by close to 20 percent in recent years, reveals another form of extraction by finance capital. The IMF program has imposed severe austerity, with high interest rates in the name of inflation targeting and reduced state spending sharply contracting the economy.

However, this has led to the appreciation of the Sri Lankan rupee, which was one of the best performing currencies last year, leading to the resumption of capital inflows. Furthermore, the IMF-arbitrated debt deal with bondholders last month uses novel macro-linked bonds in exchange for the defaulted bonds, which will result in higher debt payments if the dollar value of Sri Lanka’s GDP increases over the next two years. In other words, bondholders will be repaid more if the rupee appreciates, even though real output may not have increased.

Sri Lanka’s economy needs to grow out of the economic depression and the state has a major role to play in this expansion. However, what is at stake with GDP growth is its substance; it can be due to the building of high rise luxury condominiums that remain idle or agricultural production necessary for the immediate food needs of our people. We do need GDP growth, but it should be increased output that expands employment and livelihoods, ensures access to free education and healthcare, and a food system that nourishes our people.

(This article was originally published in the Daily Mirror on January 21, 2025)