The effectiveness of private equity has been a subject of ongoing debate in countries of…

The Zambian Debt Default: A Structuralist Perspective Howard Stein and Horman Chitonge

In November 2020, Zambia defaulted on its international debt, the first African country to do so since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic. This article criticizes the IMF’s attribution of the default to Zambia’s mismanagement and corruption. We present an alternative structural explanation, which ties the crisis to Zambia’s adoption of neoliberal policies, its extractive colonial style economy, and a problematic global financial architecture that pressures Zambia to accumulate U.S. dollars. Debt crises are likely to reoccur as long as the IMF and the governments that receive their loans continue to misinterpret the causes of financial crises like the one Zambia is experiencing.

Debt relief in Zambia has proven to be complex and elusive over the past four years, with the economy held hostage to a long-drawn out process. This failure exemplifies the woefully inadequate nature of the international financial architecture, under which many African countries have experienced several debt crises. As of July 2024, 22 African countries were either in or at a high risk of debt distress, unable to fulfill their financial obligations and in need of debt restructuring. This pattern will likely recur unless there is a fundamental rethinking of the global financial system to move away from flawed economic theories and status-quo reenforcing policies. The continued emphasis on neoliberal policies like deregulation, limiting inflation at the expense of employment, and procyclical policies only exacerbate the conditions that led to the default originally.

Default and the Debt Crisis in Zambia

Zambia, like other African countries, had faced high debt levels before 2020 due to its historical dependence on U.S. dollar denominated loans and the volatility of copper exports, the country’s main export. In 1998, Zambia’s external debt reached an unsustainable 207 percent of Gross National Income (GNI) and 715 percent of export income. The Multilateral Debt Relief Initiative (MDRI) and Highly Indebted Poor Countries Initiative (HIPC) programs, which wrote off debt in return for neoliberal policy conditionality, led to a reduction of external debt from $6.9 billion to $2.3 billion in 2006. With the recovery in exports and income, debt ratios fell to a manageable 49 percent of export income and only 20 percent of GNI.

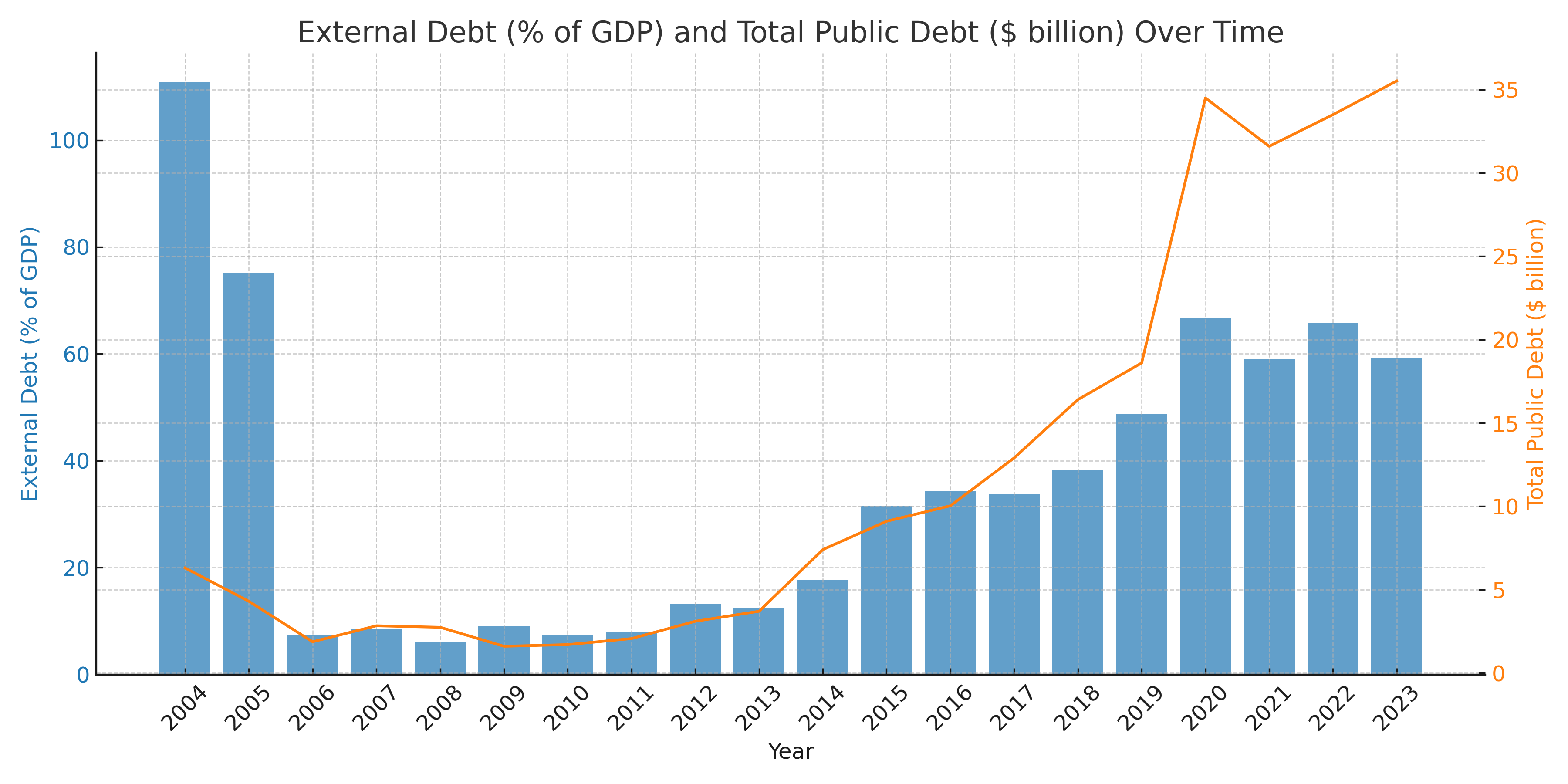

In 2013, debt returned to 1998 levels and remained moderately high relative to GNI. Debt ratios remained manageable, in part due to the rising price of copper, which accounted for roughly 70 percent of total export earnings. However, debt sustainability would not last. As shown in Figure 1, total public debt increased fourfold from 2013 to 2023, reaching $35 billion. By 2020, the debt to GNI ratio had risen dramatically to 168% up from 24.9% in 2013. Debt servicing at that level was unsustainable. In November 2020, Zambia became the first African country to default on its sovereign debt since Mozambique in 2016 after missing a payment of $42.5 million.

Figure 1: External Debt to GDP (%) and Total Public Debt ($Billion)

Source: International Debt Statistics

Figure 1 illustrates the rapid rise in total foreign debt relative to GDP and the total debt in billions, placing an impossible burden on the government’s ability to service the debt. Like many African countries, following the COVID-19 pandemic, Zambia was forced once again to turn to the IMF for financial support.

Orthodoxy and the IMF

Instead of pointing to the underlying structural conditions that created the crisis, the IMF blamed the default on Zambia’s excessive spending and poor governance, leaving the country susceptible to the pandemic’s economic shocks. The IMF then approved a 38-month Extended Credit Facility (ECF) for SDR 978.2 million (around $1.3 billion) on August 31, 2022.

The IMF conditioned the ECF on Zambia implementing several neoliberal governance priorities.[1] Among these was the government’s commitment to a new Public-Private Partnership (PPP) Act aimed at strengthening PPPs and tackling corruption. The Act would enhance private property rights, contract enforcement, and promote private sector participation in infrastructure development—neoliberal strategies that ultimately do not address the root causes of the crisis. ECF conditionality also included procyclical budgetary cuts and tax increases to generate a government surplus of 3.2 percent by 2025, up from a 6 percent deficit in 2020. Generating a surplus when an economy is in crisis is likely to exacerbate already poor living conditions since the government must remove more spending from the economy than it adds.

On the revenue side, Value-Added Tax (VAT) exemptions were removed on beverages, cement, coal, and fertilizer, increasing the prices of those goods to consumers and businesses. Subsidies on fuel, seeds, and fertilizer were also removed or curtailed, raising their prices. External debt was to be restructured through negotiations under the G20 Common Framework, which designated a creditors’ committee to resolve the credit crisis. However, additional external borrowing was limited to concessional debt, forcing Zambia to rely on multilateral and bilateral donors for financing. Furthermore, the government was not permitted to renegotiate domestic debt because it would “weaken market and business confidence.”[2] This reduced the flexibility of the government to reallocate its expenditures toward other economic and social priorities. The government was simultaneously required to keep interest rates high (26 percent in 2022), dramatically slowing monetary growth and reducing credit to the private sector, further dampening economic expansion.

Widespread evidence indicates that IMF loans tend to worsen poverty in developing countries. Although the ECF has a section devoted to social spending, its emphasis on cutting public expenditure would worsen poverty and inequality. The IMF recognized that Zambia’s poverty rate had exceeded 60 percent before the default but asserted that fiscal consolidation would free up critical resources for public spending without explaining how this would be done. Without evidence, the IMF further claimed that the net impact of removing fuel and electricity subsidies would be positive for Zambia’s poor.

Even more consequentially, the orthodox focus on imprudent government spending habits and poor governance misses the underlying structural causes of the debt crisis. During both current and past sovereign debt crises, imbalances were induced by declining copper prices, on which Zambia remains reliant. In 2022, 89.2 percent of Zambia’s exports were in unprocessed raw materials, mostly copper, only a small reduction from the 93.9 percent figure in 1995. This reliance on raw material prices causes economic swings as prices rise and drop. Without transforming this colonial-style economy, the country will likely continue to require burdensome sovereign debt restructuring.

IMF loans further entrench Zambia’s dependence on raw material exports. Like many other African countries, Zambia has a currency that seldom circulates beyond its borders. Few countries are willing to exchange their goods and services for Zambia’s currency. As such, they are under constant pressure to acquire US dollars, Euros, or Yen to finance imports. As part of the IMF conditionality, Zambia was forced to accumulate foreign exchange reserves. In fact, half of the ECF loan is simply expected to go towards building these reserves. Zambia needs IMF loan dollars to help diversify production away from raw materials by importing capital goods to advance manufacturing. However, IMF loan conditions restrict Zambia’s industrial policy and reinforce the country’s dependence on copper exports.

Policy Recommendations

While the restructuring of sovereign debt is urgently needed to provide relief, the main and long-term challenge in Zambia is to transform the colonial economy by diversifying production and export activities. The Zambian government must commit to industrial policy through a range of tools aimed at supporting manufacturing such as subsidies, tax incentives, infrastructure, workforce training, protectionist measures, and research and development. For example, the government could provide loans at subsidized interest rates in return for investments in industries beyond raw materials, following Asian development models.

Current industrial policy is highly limited in its scope and focus. The key institutions that promote industrial growth like the Zambia Development Agency (ZDA), the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), and the Citizens Economic Empowerment Commission (CEEC) mostly focus on private sector growth and deregulation. This is consistent with the ideology of mainstream economists that dominate these Industrial Policy Organizations (IPOs). Part of the problem in Zambia is the adverse impact of neoclassical economics on education that leaves policy personnel poorly equipped to promote industrialization. Zambia needs to draw on a broader set of theoretical tools to design a frontier industrial policy (FPI) with the state taking the lead in identifying strategic sectors to coordinate the flow of investment to structurally transform the Zambian economy. Using a variety of industrial policy tools, a key element of FPI is to work with other African countries to adopt and expand regional value chains with export potential.

Zambia must also develop a central coordinating agency with representatives of ministries, IPOs, and the private sector should oversee Zambia’s industrial policy framework.

International agencies like the IMF need to provide greater policy space for countries like Zambia to pursue new strategies to transform their economies. The IMF should support the structural transformation of the economy through a concerted industrial policy aimed at diversifying exports. In addition, new sources of international financing, such as the expansion of access to SDRs (Special Drawing Rights), are necessary. Created by the IMF in 1969, SDRs represent a basket of five currencies used by IMF member countries to supplement their official reserves. These increase access to global liquidity since they can be exchanged for foreign currency like US dollars or Euros. Access to SDRs would allow Zambia to build foreign exchange reserves without accumulating further debt. These are only a few of the areas that need to be addressed for Zambia to escape their vicious cycle of commodity dependence.

Conclusion

This paper has explained the reasons behind Zambia’s 2020 sovereign external debt default, focusing on the weaknesses of the IMF’s interventions, while providing an alternative structuralist explanation. The Zambian economy, like so many others on the continent, continues to rely on the export of primary commodities for foreign currency, making it vulnerable to price disruptions. While debt relief through sovereign debt restructuring is urgent, debt crises will likely reoccur without an effort to diversify the country’s production base and export activities. To achieve that goal, Zambia will need to develop a new set of policies and institutions that can support the growth of the manufacturing and logistics sectors. Most importantly, the IMF must rethink the orthodoxies that currently prevail and impede economic progress in countries like Zambia.

[1] In the 1990s, the IMF expanded their conditionality to include reforms related to improving government accountability, transparency and the rule of law with the argument that it would encourage economic growth by providing an improved environment for private sector investment. The theoretical and empirical foundation has been problematic as has the exact specification of which policies constitute governance conditionality.

[2] The Common Framework for the first time brings together official (including China) and private debt holders to deal with foreign debt. However, the international holders of domestic debt are not part of this group. Domestic debt strategies come under the purvey of the conditionality of the IMF and hence they are able to constrain the Zambia government from renegotiating domestic debt.

. . . . . . . .

Howard Stein is a Professor in the Department of Afroamerican and African Studies (DAAS) and the Dept. of Epidemiology at the University of Michigan. He is a development economist educated in Canada, the U.S. and the U.K. He has published more than a dozen books and edited collections and more than 125 journal articles, book chapters and reviews. He has held various academic appointments in Africa and Europe such as the University of Dar Es Salaam, Tanzania; Hitotsubashi University, Japan; Sussex University, UK; Trinity College, Ireland; University of Lisbon, Portugal; and University of Leiden, Netherlands. He has undertaken research in a variety of African countries on topics like foreign aid, finance and banking, neoliberalism, the methodology of Randomized Controlled Trials, health and gender, climate change, industrial policy, export processing zones, agricultural policy, African overpayment on sovereign bond issues, poverty and rural property right transformation, income inequality, Chinese economic relations and the institutionalization of neoclassical economics.

Horman Chitonge is Professor at the Centre for African Studies and research associate at PRISM, School of Economics University of Cape Town (UCT). He is a visiting research fellow in the Global Justice Programme, Yale University, and a visiting professor at the African Studies Centre, Tokyo University of Foreign Studies. His research interests include agrarian political economy and alternative strategies for economic growth in Africa. His most recent books include: Oxford Handbook of the Zambia Economy (Oxford University Press, 2024) Industrial Policy and the Transformation of the Colonial Economy in Africa (Routledge, 2021). Industrialising Africa: Unlocking the Economic Potential of the Continent (Peter Lang, 2019).

(This article was originally published in Georgetown Journal of International Affairs on January 9, 2025)