The victory of the National People’s Power (NPP) candidate, Anura Kumara Dissanayake, in the Sri…

Fiscal Stringency in a Time of Pandemic C. P. Chandrasekhar and Jayati Ghosh

Through out the continuing pandemic, the Indian government’s fiscal reticence has made it a significant outlier in the world. Advanced economies have gone all out in terms of expanded public spending. Their governments quickly abandoned the (flawed) arguments about the dangers of large fiscal deficits, when large capitalists realised that they would also suffer from the closures and downturns created by the spread of the coronavirus.

Even governments in developing countries constrained by external debt overhang and fear of capital flight increased their spending despite declining revenues, both to provide some relief and social protection to their populations, and to shore up domestic demand that would otherwise collapse completely. While their additional spending was only a tiny fraction of that in the rich world, and not even very much in relation to GDP, it was nevertheless on average a notable increase over the immediate past.

Not so in India, unfortunately. The Indian government is one of the few in the world that voluntarily reduced its total spending in this crisis period. And it did so even though it was not constrained by sovereign debt concerns or conditionalities imposed by multilateral organisations. the central government is so obsessed with the need for fiscal discipline, no matter what the context or requirements of particular exigencies, that any reduction in total revenues causes it to cut down on its spending.

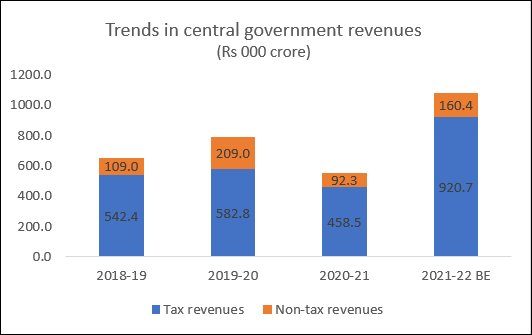

It was entirely predictable that the questionably harsh yet ineffective lockdown in mid-2020 and then the spread of the second wave from early 2021 would have severe impacts on economic activity. This obviously led to declining revenues for the government. Figure 1 shows that total receipts of the government fell by more than 30 per cent, although tax revenues fell by only around 22 per cent. This lower impact on tax revenues was partly because of the revenues from enhanced levies on petrol and diesel that the Centre did not share with state governments, and partly because large companies continued to flourish and even benefited at the expense of smaller companies in this period.

Figure 1

Source for Figures 1-3: Statement on half yearly review of the trends in receipts

and expenditure in relation to the budget at the end of the first half of the financial year 2021-22,

Ministry of Finance, Government of India,

https://dea.gov.in/sites/default/files/H1%202021-22%20FRBM%20English.pdf

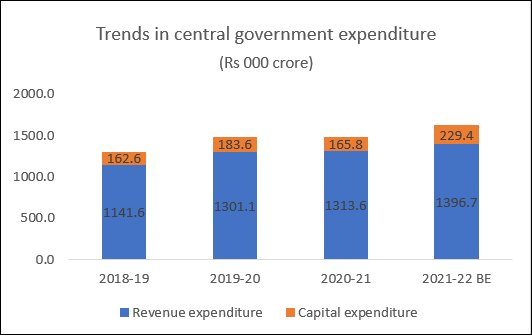

Figure 2

State revenues declined across the world, but most governments increased their spending anyway, because the economic and health crises clearly warranted higher public expenditure. However, as indicated in Figure 2, the Indian government actually spent Rs 5,300 crore less in pandemic year 2020-21 than in the previous year. This was notwithstanding the claims made in the various relief packages announced over the year. For example, the Atmanirbhar Abhiyan package of May 2020 was claimed to amount to an additional Rs 10 lakh crore, or 10 per cent of India’s estimated GDP. Obviously, this was nothing more than a smoke and mirrors exercise, as the government cut down on other (often crucial) areas of spending to compensate for small increases such as in the rural employment programme.

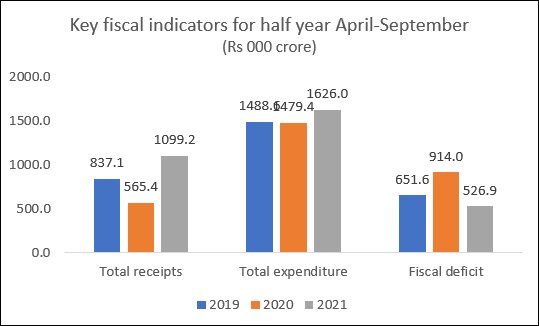

This extraordinary fiscal stringency has continued into the current financial year, despite the collapse of employment and livelihoods and the still-dire situation faced by most working families. Figure 3 compares the main fiscal indicators across the first half of the financial years since 2019-20.

During the brutal lockdown of March-July 2020, when enhanced public spending was most required, public spending was lower than for the same period of the previous year, by more than Rs 9,000 crore. Even in the current year, expenditure has been restrained, showing very little increase (7.8 per cent) in nominal terms compared to two years earlier, and stagnating in real terms when inflation is taken into account.

In the current year, spending remains low even though revenues have been much more buoyant, driven by an increase in direct tax receipts of 84 per cent compared to the previous year. This increase could reflect a bigger cause for worry: a dramatic increase in economic inequality. Income concentration has been rapid and extreme, with the top 10 per cent and even 1 per cent grabbing larger shares of the pie. Meanwhile, micro and small enterprises have been closing in droves, and self-employed people have been losing their incomes, with their market shares being taken over by large companies that pay more direct taxes. Restrained spending and rising revenues have led to a significantly lower fiscal deficit, which sems to have been the government’s primary aim, regardless of the economic cost to the citizenry.

Figure 3

This is bad news for the macroeconomy. The impact may be temporarily disguised by the greater profits made by some large corporates, and rising asset values driven by growing inequality, but soon enough the overall impact of low public spending on depressed domestic demand and inadequate infrastructure will be felt.

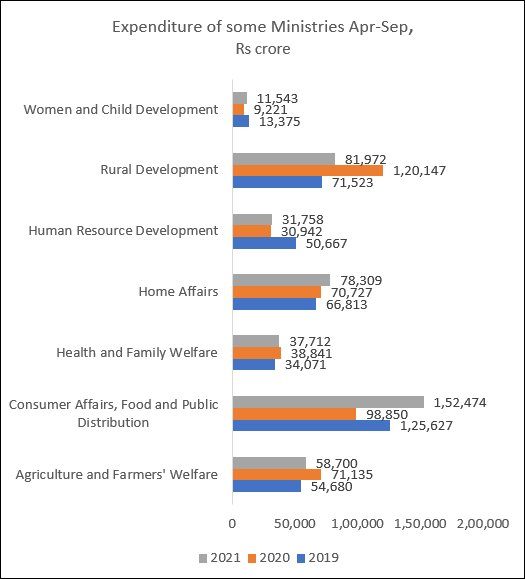

Low spending also affects the public provision of essential goods and services. Figure 4 presents trends in spending by some crucial ministries over the first six months of the current and past two financial years, as shown in Figure 4. Some of these Ministries provide funding for central schemes that are absolutely crucial for health, livelihoods and basic public services like education.

Figure 4

Source: as above and https://cga.nic.in/MonthlyReport/Published/9/2019-2020.aspx for 2019.

The pattern of public spending on these Ministries is an indication of the extent to which citizens’ rights are met by the state. Some of the starkest indicators relate to employment, food access, health and education. Most countries increased spending on both health and education during the pandemic, which created more demands on health services and required large investments to compensate for school closures and enable the sudden shift to online learning. Not so in India. Health spending has remained pitifully small, and even fell in nominal terms in the first half of this year compared to last year. (Note that it is around half of the spending of the Ministry of Home Affairs—truly remarkable in a country where state governments are supposed to be responsible for security). Education spending by the Ministry of Human Resource Development fell sharply during the pandemic instead of increasing, and still remains at less than two thirds of pre-pandemic spending, meaning that we are effectively denying a generation of children and youth their right to education. The spending on women and children, which provides essential nutrition to mothers and infants, was similarly cut and remains well below pre-pandemic spending. Spending on agriculture fell this year, in the teeth of the ultimately victorious farmers’ struggle.

The Ministry of Rural Development is responsible for a number of schemes that directly affect livelihood, most important of which is based on the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MNREGA). In the peak of the first wave, spending on this clearly increased. But labour market conditions are still terrible in rural India, and the total spending on this has fallen sharply in the current year. Spending on public provision of food appears to have increased in the current year, but this is really a statistical artefact: it reflects the fact that the central government finally paid up some of the longstanding dues it owes to the Food Corporation of India from previous years.

It is hard to explain this pattern of public spending in a democracy. Whatever may be the factors driving it, the people of India will be paying the costs of this for years to come.

(This article was originally published in the Business Line on December 27, 2021)