Hearing a petition on November 22 to remove the term “socialism” from the Preamble of…

WTO is Using COVID for its Expansionist Free Trade Agenda Murali Kallummal and Smitha Francis

As the world is reeling under the deaths and exponential spread of the COVID pandemic, the World Trade Organisation (WTO) is busy negotiating a free trade deal in electronic medical equipments. One of the five proposals made to the WTO’s Council for Trade in Goods for combating the pandemic include “removing the impediments to trade in essential products to ensure their free flow”. Other objectives of such COVID-related proposals by 25 countries include: commitment to ensuring supply chain connectivity; predictable trade in agricultural products and food; and declaration of trade in essential goods.

While the proposals made by other countries are generic in nature, New Zealand and Singapore have notified a Declaration on Trade in Essential Goods for Combating the Covid-19 Pandemic (“the Declaration”) dated 16 April 2020. The joint Declaration covers tariff elimination as well as harmonisation of other import and export measures. It requires any WTO member accepting the Declaration to eliminate all customs duties and all other duties, and to refrain from adopting non-tariff barriers, for a list of essential goods provided in two Annexes. Annexe I contains 124 products belonging to four product groups – medicines, medical supplies, medical equipment and personal protection products. Annexe II has an additional list of 180 products, which are mainly agricultural products. On 3rd April 2020, the WTO secretariat had already released a study, which provided an assessment on 96 products, with an intention liberalise the trade in medical products. This list also includes electronic medical devices and equipment.

Thus the general objective of both the Declaration and the study appears to be an effort to expand the coverage of the plurilateral (sectoral) agreements, the “Pharma Agreement” and the Information Technology Agreement (ITA). Plurilateral agreements are agreements negotiated between smaller groups of countries under the WTO.

Trade negotiations are all about timing. These efforts once again bring to the forefront that the WTO negotiations are not about development and sustainability – they are about protecting and promoting developed country commercial interests, as they have always been.

Once again, the current focus is also largely on tariff elimination. The two proponents – Singapore and New Zealand, who have called for free trade in these “essential goods”, together do not account for more than 3% share in total global medical equipment imports. Further, with Singapore’s MFN duties at 0% and New Zealand’s average applied MFN duty on medical equipments at 0.8%, tariff elimination does not stand to disrupt their domestic producers. Developed countries mostly depend on domestic regulations and standards to regulate imports.

Unfortunately, tariffs (ad-valorem) remain the prominent barrier for imports into developing countries. For instance, India’s average applied MFN duty for medical equipment stood at about 9%.

Thus bringing down the tariff duty only serves to enable greater access for producer firms – mainly from the developed countries, to our markets. Increasing import competition at a time of economic distress from the national lockdown will be at the loss of our domestic producer firms of medical equipment. The usage of domestic regulations and standards, which would have addressed our concerns in the absence of tariffs, is sparse across the developing world.

During the emergency caused by the pandemic, the WTO may have a role to act on the removal of supply chain disruptions in essential medical and agricultural goods. However, the elimination of tariffs is the least of its immediate concerns. Importing countries with higher duties on medical products (and high import requirements during this period) can unilaterally decide to bring them down temporarily, factoring in the concerns of their domestic industry. On the contrary, there is a need to address the concerns of SME exporters from developing countries, which include higher industry standards in the developed countries and compliance with third-party certification requirements. The route being adopted at the WTO presently only highlights the agenda of the developed world.

India was a willing participant to the first Information Technology Agreement (ITA-1) eliminating tariffs on 217 IT products. This was concluded in 1995 between 82 members representing about 97 per cent of world trade in IT products. At the Nairobi Ministerial Conference in December 2015, over 50 members concluded the expansion of this Agreement, which now covers an additional 201 products valued at over $1.3 trillion per year. Having learned its lessons from the disastrous impact of the ITA-1 on the domestic IT hardware manufacturing producers, India did not become a party to the ITA-expansion Agreement.

The possibility of a Medical Goods Agreement would mean the merging of two plurilaterals – the Pharma Agreement and the ITA-expansion Agreement, as it covers 11 per cent products under the ITA-expansion Agreement. The other dimension to the present medical goods proposal is that it has products that were also present in the NAMA Healthcare Sector sectoral proposal of 2008. The Declaration list covers 25% of the products in the NAMA Sectoral. Both of these clearly point towards the beginning of the expanding coverage for trade liberalisation targeted at large markets like India.

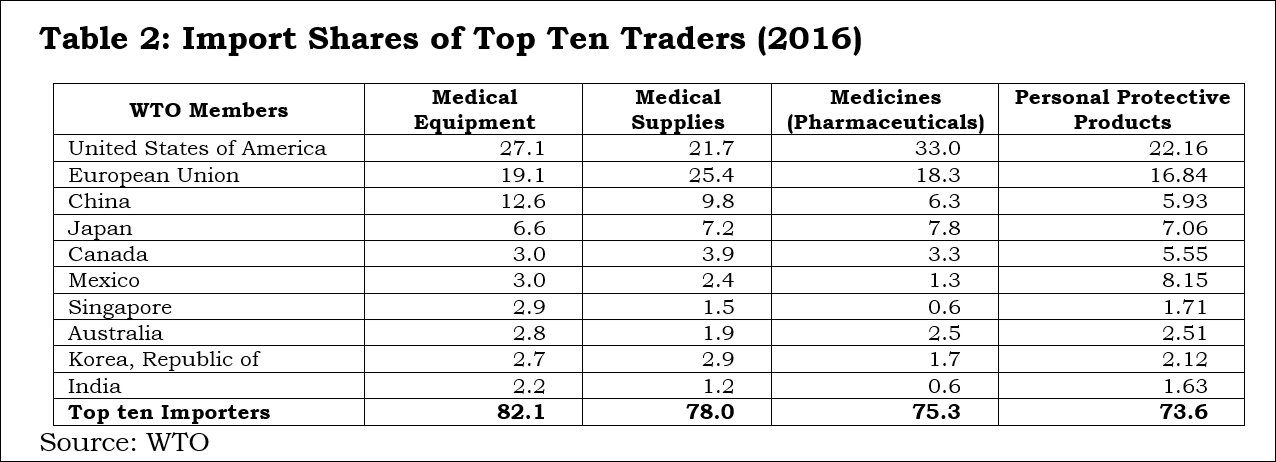

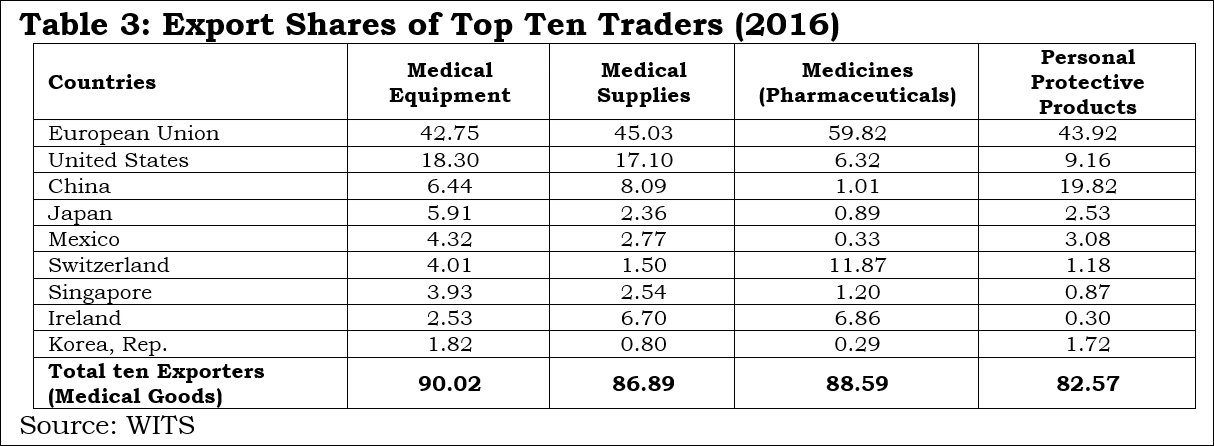

Tables 2 and 3 clearly indicate the process of “facilitation” done by the WTO for a few countries. Any liberalisation by participating countries under the Declaration would facilitate countries like the EU, US, China, Japan, Mexico, Switzerland, Singapore, Ireland and Korea, which accounted for 90 percent of global exports in medical equipmment. Among these, China is the only developing country with supplying capacities; and it is well known that the value addition by MNCs in Chinese manufacturing is rather low.

India does import 2.2% of medical equipment, but its export share is only 0.5%; therefore it would not be wise for India to join this Declaration. Similar to the 1996 plurilateral (ITA-1), tariff liberalisation without industrial policy support, including domestic-oriented technical regulations and standards, will virtually wipe out the production capacities in developing countries like India in medical equipment.

The above tables also indicate the pattern of very high demand and supply between USA, EU, China, Japan, Canada, Mexico, Singapore and South Korea. Rather than proposing any agreement on medical goods, these countries should have bilateral deals!

The suppliers (firms) that have benefitted from tariff-only trade liberalisation carried out under the WTO so far have mostly been from the developed world, which offer products meeting the regulatory standards made by the International Standards Organisation (ISO) or private Industry bodies or associations. With these product standards being tweeked by the lead firm/industrial assotiation/exporting country, all WTO negotiations are purely commercial deals. In the absence of appropriate disciplining of non-tariff measures at the global level, countries like the EU, Switzerland, Japan and the US will be allowed a free run in supplying about 71% of the global medical equipment market.

All 135 products under the medical goods (combined list of products from the WTO study and the Declaration) are essential. However, for India, electronics and medical products are both strategic sectors. Therefore, taking on the onus of further tariff-only liberalisation under any proposal at the WTO, without national industry-specific standards, will not serve India’s strategic interests.

The developed members are attempting to play the old tricks, which some of them have mastered over more than seven decades of international trade negotiations. This is a reminder to the South that even in a pandemic, the North is only bothered about consolidating the market shares of their firms. The developing and less developed countries have to guard against old ways creeping into the emerging world trade rules. This calls for an urgent need to reform the organisation to get rid of data gaps and information asymmetry.

* Murali Kallummal is Professor, Centre for WTO Studies, IIFT, and Smitha Francis is Consultant, Institute for Studies in Industrial Development (ISID), New Delhi.

(This article was originally published on 1 May 2020 at https://www.policycircle.org/economy/wto-using-covid-to-push-expansionist-free-trade-agenda/)